- Research article

- Open access

- Published:

A conceptual framework for understanding the intrinsic contestation of cultural heritage tourism in Chinese qiaoxiang

Built Heritage volume 6, Article number: 28 (2022)

Abstract

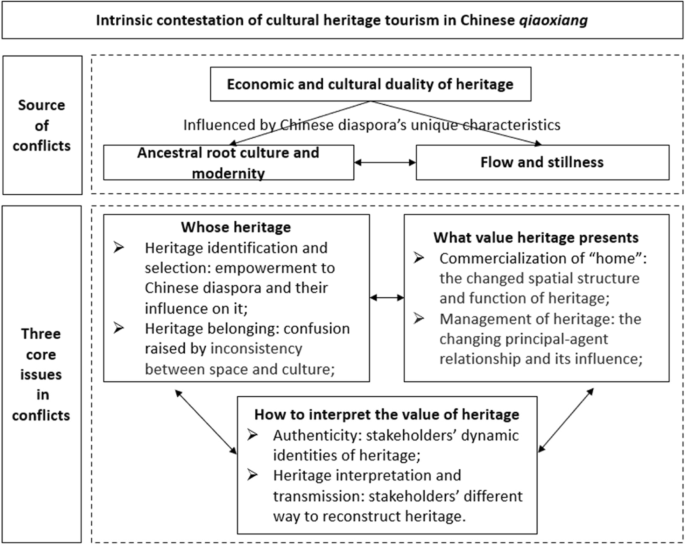

Cultural heritage in Chinese qiaoxiang is constructed where Chinese and foreign cultures gather, connecting overseas Chinese with their country of origin. However, conflicts concerning this type of heritage comes out frequently, such as house reconstruction clash, host-guest conflicts and destructive competition in heritage tourism. The economic and cultural duality of heritage is perceived as the source of intrinsic contestation in heritage tourism, and conflicts related to different types of heritage may take on different appearances and causes. Extant tourism studies have generalised cultural heritage in Chinese qiaoxiang, neglecting the unique characteristics of the diaspora and their corresponding influence on heritage protection and utilisation, that makes the reasons for these conflicts remain unclear. By answering the basic question of what heritage is, this research proposes an analytical framework to understand the intrinsic contestation of cultural heritage tourism in Chinese qiaoxiang. The paper points out that the contradiction between ‘ancestral root culture’ and modernity and between flow and stillness is the trigger for intrinsic contestation. The paper also summarises the core issues in conflicts that need further discussion by answering the questions of ‘what is heritage’, ‘whose heritage’ and ‘how to interpret heritage’. The core issues include heritage selection and identification, the commercialisation of ‘home’, heritage interpretation and so on.

1 Introduction

There are three main relationship types between heritage and tourism: automatically harmonious, inevitably in conflict, and potentially sustainable (Ashworth 2000). The inevitable conflicts of heritage tourism have been under academic scrutiny for the past 30 years. Researchers have reached a general consensus that the economic and cultural duality of heritage can cause a power imbalance among stakeholders, leading to conflicts in heritage tourism (Graham et al. 2000). The economic and cultural duality of heritage is also perceived as the source of intrinsic contestation in heritage tourism (Peckham 2003).

Conflicts related to different types of heritage may take on different appearances and causes (Dahrendorf, 2000). The cultural heritage in Chinese qiaoxiang is such a special type. It was born from a unique social structure which the diaspora brought about, distinctively different from other native-place concepts of heritage (Clifford 1995). Here, the term ‘Chinese qiaoxiang’ refers to the birth and living place of overseas Chinese before they go abroad. The Chinatowns and overseas Chinese farms (in the 1960s, some Southeast Asian countries expelled ethnic Chinese, and the overseas Chinese farms were where the returned overseas Chinese and refugees were accepted and resettled in China) that were built outside the ancestral hometowns of overseas Chinese are not included in this discussion. The cultural heritage of Chinese qiaoxiang mainly refers to houses in China built using remittances from overseas family between the late 19th century and the 1930s. The diaolou and qilou in China’s Guangdong Province are typical examples of these buildings. Due to the long diasporic history of overseas Chinese, these cultural heritage sites are often spatially separated from their owners and influenced by many unresolved historical issues (including takeovers during land reforms), further complicating the question of property rights. There are also numerous successors of the original diaspora sharing a claim to property rights, often with heavy emotional involvement (Chen 2001). These unique characteristics of the cultural heritage in Chinese qiaoxiang lead to conflicts related to heritage protection and utilisation, such as the contradiction between private property rights involving heritage sites and the argument that heritage should be accessible to all people and politically sensitive issues in the use of heritage resources.

However, previous research tends to generalise the cultural heritage in Chinese qiaoxiang with minimal effort to examine the uniqueness of the diaspora involved and how involvement from these different overseas communities influences the specific point of contestation. Some researchers have noticed the influence of the diaspora and have responded with studies aimed at analysing the change in how residents perceive their hometowns (Zhang and Deng 2009) and the reproduction of community space for tourism purposes (Sun and Zhou 2014). However, the Chinese diaspora’s power to influence heritage construction and interpretation is still largely ignored, even though it may lead to different conflicts in heritage tourism. Therefore, this paper attempts to highlight the uniqueness of cultural heritage tourism in Chinese qiaoxiang and proposes a conceptual framework to understand this unique heritage type.

2 The intrinsic contestation of heritage tourism

2.1 Heritage tourism and the intrinsic contestation

The word ‘heritage’ originates from Latin in which it referred to the father’s legacy. Even after the passage of centuries since its origin, heritage has not significantly changed its connotations and largely retains its original meaning (Zhang 2008). Current common concepts in heritage studies, such as ‘cultural heritage’ and ‘natural heritage’, were first formally defined in the ‘Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage’ by UNESCO on November 23, 1972. At this convention, heritage was classified as monuments, buildings, and ruins (Wang 2010). However, the scope of heritage has been broadened and diversified since the mid-1980s; local cultural and historical figures have been included in the heritage category, with increasingly acknowledgement of the heritage traditions of the general public (Corner and Harvey 1991). Moreover, intangible cultural heritage has received increased attention since UNESCO’s announcement of the ‘Recommendation on the Safeguarding of Traditional Culture and Folklore’ in 1989, the ‘Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity’ in 2001 and the ‘Istanbul Declaration’ in 2002. These movements signify a change in the connotations of heritage beyond physical artefacts such as treasures, antiques, and cultural relics to intangible forms of heritage such as cultural practices.

Concerning the complexity of the dynamic nature of heritage and tourism, McKercher, Ho, and Du Cros (2005) put forwards seven possible relationships in cultural heritage management and tourism: denial, unrealistic expectation, parallel existence, conflict, imposed comanagement, partnership, and cross-purposes. Most studies regard the relationship between heritage and tourism as one of ‘contradictions and conflicts’ (Nuryanti 1996; Robinson and Priscilla 1999). Ashworth and Larkham (1994) argue that heritage is both an economic resource and cultural capital under the new sociopolitical and economic background. The economic part is shown in the development of the heritage industry. The cultural part is represented in heritage’s connection to place and time, which helps remind and strengthen a sense of meaning and purpose for individual humans, groups, and even nations. There is also an inseparable relationship between heritage and identity (Peckham 2003). The economic and cultural duality of heritage leads to contradictions in heritage tourism, resulting in the intrinsic contestation of heritage tourism (Graham et al. 2000). Because of this duality, stakeholders fight for power and resources in the process of producing and consuming heritage, inevitably leading to conflicts (Peckham 2003). Robinson and Priscilla (1999) propose a conceptual framework in which imbalanced power distribution in heritage tourism is the root of all contradictions. Based on Robinson’s framework and the inclusion of politics in heritage tourism, Graham et al. (2000) believe that stakeholders’ different power statuses and their distinct value orientations towards heritage utilisation create the source of contradictions over how best to handle heritage sites, ultimately resulting in the inherently contradictory nature of heritage tourism. For example, experts such as archaeologists, museum curators, and architects led the authoritative discourse on heritage in the past. The value of heritage was technically verified and evaluated by expert analysis of the material part of the heritage, and the correct transmission and inheritance of heritage required expert intervention. At this point, physical heritage artefacts were mainly preserved. With the emergence of the international critical heritage research trend in the 1990s, the construction of heritage was highlighted, and the ‘democratisation’ of heritage was respected. Heritage and democracy have become new topics in international heritage protection. ‘The Delhi Declaration’, adopted at the 19th ICOMOS Conference in 2017, called for promoting an inclusive democratic community process – elected by people and governed by and for the people – and emphasised the idea that heritage belongs to all. Traditional heritage production and consumption dominated by elitist narratives of validation were thereby threatened (Smith 2003; Walsh 1992). When authorities try to force others into their own discursive system of heritage protection, the inconsistency of value cognition often results in conflicts in heritage practice.

2.2 Three core issues in heritage tourism

Based on the above discussion, Peckham (2003) built a theoretical framework of intrinsic contestations. There are three contested aspects: multiple values of heritage, multiple interpretations of heritage, and the production and consumption of heritage. These three aspects highlight three core issues in the intrinsic contestation of heritage tourism: ‘whose heritage’, ‘what value heritage presents’, and ‘how to interpret the value of heritage’.

‘Whose heritage’ is mainly concerned with the stakeholders involved in heritage tourism. This can be explained through the production and consumption of heritage. Heritage production is the valuable historical accumulation of natural evolution and human civilisation, but not all production can be regarded as heritage (Xu 2005; Hornby 2005). What is retained, replaced, and emphasised among numerous resources results from power manipulated for different purposes (Peng and Zheng 2008). Usually, heritage identification and declaration are determined by international value systems and the validation by domestic experts (Dai and Que 2012), such as UNESCO, domestic governments, and heritage experts. These experts dominate the heritage discourse and highlight a top-down process of constructing heritage production (Zhao 2018a, 2018b). Thus, even though members of the general population, such as local communities, may be the actual builder of a heritage artefact, they may not be able to control the heritagisation and touristification process and remain marginalised in heritage production. In terms of heritage consumption, the role of mass consumers starts to emerge as they are no longer passive recipients of heritage production but consumers whose preferences influence the content and representation of heritage (Hu 2011). For example, the construction of Zhouzhuang and Wuzhen in China considered the demands of tourists during the transformation of heritage into tourist commodities (Zhang et al. 2008). The standard of authenticity for architectural heritage in Hong Village, China, was also influenced by stakeholders such as administrative and social elites. As various stakeholders become involved in heritage production and consumption, their different identities may trigger conflict and spark fierce contestation on who has the authority to decide what heritage is and its selection criterion (Zhang and Li 2016).

‘What value heritage represents’ is mainly about the responses to the economic and cultural duality of heritage tourism (Hu 2011). Heritage transmits its cultural values through economic behaviours, and the economic value created in the process also fosters the generation of cultural identities. However, stakeholders in heritage practice have their individual stances that lead to different preferences for economic and cultural attributes of the heritage, thereby affecting the representation of the heritage value. At this point, heritage is actually determined by a cultural process rather than proof of its simple physical existence (Harvey 2001), as questions such as representation (‘whose heritage) and value interpretation (Zhang and Li 2016) are put forwards. Behind the representation of historical value, the power game among stakeholders continues.

‘How to interpret the value of heritage’ is mainly about how to give and disseminate meaning onto material representations of heritage. Tilden (2009) first raised the issue of interpretation in heritage protection in the book ‘Interpreting Our Heritage’. Tilden believes that ‘understanding could be achieved through interpretation, appreciation could be achieved through understanding, and protection behaviour could be generated after appreciation’. Regardless of the type of heritage, it is necessary to let the public understand its value through interpretation. When considering heritage interpretation, it is about how to tell the story, who will tell the story and to whom the story is told. In interpreting heritage tourism, the purpose of storytelling is to yield economic benefits. Authorities and commercial organisations become the main storytellers telling the story to public consumers. The story itself has turned into a kind of ‘discourse of power’ (Peng and Zheng 2008), with questions such as how to interpret and construct heritage and how tourism affects the heritage site and its interpretation (Zhang and Li 2016).

This framework shows the source of intrinsic contestations in heritage tourism, and the three core issues it emphasises also depict specific conflicts during heritage production and consumption. This framework is also accepted and adapted in heritage tourism studies (Hu 2011; Zhang and Li 2016). Accordingly, the paper also adapts this framework to illuminate the intrinsic contestation of cultural heritage tourism in Chinese qiaoxiang.

3 The uniqueness of cultural heritage tourism in Chinese qiaoxiang

3.1 Diaspora and cultural heritage in Chinese qiaoxiang

The diaspora is a complex and dynamic concept that was born 2500 years ago (Duan 2013). Etymologically, ‘diaspora’ consists of the word ‘sperio’ in Greek, meaning sowing seeds everywhere, and the prefix ‘dida’, referring to passing through. It was originally used to describe Jews scattered outside Palestine after the Babylonian exile, expressing a sense of being expelled or replaced. Currently, ‘diaspora’ is extended beyond its original point of reference (i.e., Jews) to refer generally to groups living outside their ancestral homeland. These groups usually maintain material or emotional ties with their motherland despite having adapted to the environment and institutions of their current country of residence (Esman 2009). Along with the emergence of nation-states, the phenomenon of migration has been given new meanings. The concept of diaspora expresses migrants’ attachment and identification with their homeland. Brubaker (2005) summarises the basic characteristics of the diaspora: departure from one’s place of origin, with the possibility of returning home, and the maintenance of a boundary between the diasporic group and the host society. That is, the concept of diaspora is considered as a trinity of the home country, the settled country and diasporic groups (Esman 2009). The rich connotations of the term diaspora also attract the interest of geographic scholars, and concepts such as transnational community (Portes 1996), transnational social fields (Levitt and Schiller 2004) and transnational social space (Faist 2000) have been created to discuss the transnational phenomenon created by diasporas. Anthropologists suggest that overseas Chinese are seen as a diaspora group in terms of their status and business networks. The transnational spatial distribution of overseas Chinese makes the migrant heritage and surrounding space a prism for group migration and mobility, showing the overlapping area of migration and ethnic research under the global cultural approach (Tuan 1977). The old barriers, such as space and national boundaries, are gradually broken, and migrant heritage in the homeland of overseas Chinese people functions as a carrier for the flow of material, culture and emotion, bringing changes to the traditional static local relationship. The Chinese diaspora builds an interrelated social field in the flow and gives birth to the reproduction of local culture (Zhang 2017).

The cultural heritage in Chinese qiaoxiang was born in such an interrelated social environment. First, such heritage differs from traditional cultural heritage, which is located within the territory of a country and helps to build a national identity (Evans 2002). Cultural heritage in qiaoxiang mainly consisted of houses brimming with international elements, such as diaolou and qilou in Kaiping, Guangdong Province of China. The historical houses were often built and funded using remittances from overseas Chinese. Additionally, the then-overseas Chinese provided postcards of foreign architecture for local craftsmen as references (Zhang 2004, 2006). Thus, the architecture of diaolou demonstrated a fusion of Chinese and Western culture. Presently, the Diaolou Museum in Liyuan, Kaiping, still displays two sets of postcards of ancient Western buildings brought back by overseas Chinese in their early years. These postcards bear witness to the transnational flows of resources and people (Erdal 2012). The mix of international cultures makes it an ambivalent heritage showing the intrinsic uncertainty entailed in heritage production, utilisation and meaning-making (Wang 2021).

Second, cultural heritage in Chinese qiaoxiang conveys rich meaning to the Chinese diaspora. Influenced by the traditional Chinese philosophy of ‘fallen leaves returning to their roots’ (i.e., to return to one’s place of origin), the Chinese diaspora were eager to return to their original homeland, explaining why they were willing to spend large amounts of money building qiaoxiang houses. For them, their hometowns and belongings left in the homeland represented their roots, spiritual homes and ties connecting them and their ancestral country (Maruyama and Stronza 2012; Maruyama 2015). Hence, homecoming tourism among the diaspora became a way to identify the collective national and ethnic identity connecting the diaspora and their ancestral country (Ari and Mittelberg 2008). They return to Chinese qiaoxiang to visit, expecting everything here to be the same as in memory. Additionally, they hope to spread the value of Chinese qiaoxiang and its cultural heritage to the world, as seen in the world heritage declaration process of Kaiping diaolou and villages. Diaolou’s application for World Heritage status was not favoured initially because its construction style was considered strange, and the historical period of construction was not long ago. In terms of architectural value, it did not meet the criteria for World Heritage (Huang et al. 2007). To promote the application, the local government of Kaiping sought help from overseas Chinese. The overseas Chinese in the United States submitted a joint letter to the State Administration of Cultural Heritage to highlight the value of diaolou, which attracted attention at the national level. Then, they contacted UNESCO experts and invited them to verify the value of diaolou as an example of world heritage. Chinese overseas leaders, such as Fang Chuangjie, chairman of the Chinese Association in the United States, also wrote to UNESCO to express his support. These measures have greatly helped to realise the designation of world heritage status for qiaoxiang.

Third, cultural heritage in Chinese qiaoxiang is greatly influenced by the change in government policies towards overseas Chinese houses. The houses of overseas Chinese, such as diaolou and qilou, were turned over to collective ownership in the land reform around 1956, as they were considered the property of ‘landlords’, even though the owners were overseas. A number of overseas Chinese thus abandoned their ancestral homes and businesses and went abroad out of concern for their personal safety. After the economic reform and opening up in 1978, the Chinese government gradually implemented a policy recognising and returning housing such as the diaolou to their overseas Chinese owners. As seen, the policies towards overseas Chinese houses have been improved. However, most of the original owners had passed away with their descendants scattered around the world, and some diaolou are presently unoccupied or dilapidated due to long-term neglect. This brings property rights problems to the subsequent adaptive use of cultural heritage.

Fourth, the management of this type of cultural heritage is more complicated because of the reasons mentioned above. Many inheritors of these physical historical relics are living abroad. Therefore, the management of cultural heritage relies on the principal-agent relationship among relatives and friends. The owners often entrust family members in the village with a series of rights, such as use, operation and income, and the right of disposal, to help manage the historical property. The geographical advantages of the agents enable them to gradually dominate these resources, leading to conflicts in the process of converting them for tourism (Jiang and Zhang 2021). During the expropriation of the qilou in Chikan Ancient Town in approximately 2017, there were cases where the agent pretended to be the property owner to claim the expropriation subsidy.

3.2 The source of intrinsic contestation for cultural heritage and tourism in Chinese qiaoxiang

As discussed above, economic and cultural duality is the source of intrinsic contestation in heritage tourism. The duality is often manifested as the contradiction between protection and development, which is seen as the cause of various conflicts in heritage tourism (Zhang 2010). Influenced by the transnational and cross-cultural characteristics of the Chinese diaspora, the conflicts aroused by the economic and cultural duality may reflect differently in cultural heritage tourism of Chinese qiaoxiang. Based on the uniqueness of cultural heritage tourism in Chinese qiaoxiang, the specific source of intrinsic contestation can be depicted from the following aspects, such as the contradiction between ‘ancestral root culture’ and modernity. People experience ancient places and objects through feelings and emotions (Byrne 2013; Waterton and Watson 2013) and generate attachment to places based on past experiences. Therefore, objects often become a stimulus, triggering memories of related history (Byrne 2016a, 2016b). The cultural heritage in Chinese qiaoxiang serves such functions as it portrays a link with the overseas Chinese and conveys memories of and feelings for of the homeland and elders who have passed on. Tuan (1990) highlights the concept of ‘place attachment’ and suggests that the diaspora living abroad could reconnect with the culture and society of their hometown through tourism of their ancestral home, thereby inspiring them to develop, deepen or alienate attachment and identification with their homeland. Migrant heritage has surpassed its original function (Meskell 2004) by entering into interactions with local people and even appearing as a substitute for the ‘absence’ of the Chinese diaspora in the homeland (Byrne 2016a, 2016b). However, such ‘ancestral root culture’ has been gradually impacted by modernity. The intensification of migration worldwide has increased communication between the Chinese diaspora and the outside world during modernisation. The immigrant heritage and its local boundaries have been blurred during the course of reform, resulting in the loss of local culture (King and Christou 2011). The local connection and cultural identity of the emigrant Chinese diaspora are both challenged. Diasporic Chinese may try to maintain traditional culture (Muhammad 2017), but their cultivation of their ‘roots’ increasingly occurs without the original material carrier. Achieving harmonious coexistence and identification among multiple cultures and constructing an intercultural world have become significant problems (Zhang et al. 2018). On the other hand, the market economy, the government, the experts and scholars, the new technologies and the traditional local culture, etc., continue to lead the ‘heritage movement’ (Fang 2008). The desire of other interest groups for development of the local economy conflicts with the place attachment of the Chinese diaspora, which increases the difficulty for the Chinese diaspora to retain its original authentic ‘heritage’.

The other contradiction is between flow and stillness. On the one hand, there is confusion regarding place identity. Previous studies on heritage were limited to a boundary perspective (Levitt and Schiller 2004), arguing that heritage is produced within the scale of power relations and used to create a stable and well-defined national identity (Innocenti 2013). The Chinatowns in foreign countries go beyond the host nation’s borders and functions as a tool to establish the national identity of the diaspora’s ancestral country instead of the living country (Byrne 2016a, 2016b). Nikielska-Sekula (2019) terms this ‘migrating heritage’ and highlights how immigrants and their children born in new homeland use their ancestral heritage to maintain group identity. Although the heritage in Chinese qiaoxiang is within the boundary of the diaspora’s ancestral country, it also illustrates the culture of foreign countries. This mixture generates a unique cultural identity partly influenced by Western values, which can be seen in the discussion of the diaspora’s state of homelessness. On the other hand, heritage is often presented as material culture, continuously producing new interpretations and understandings over time. The dissemination of a static interpretation of heritage completed by different stakeholders (Merriman 2004) also cannot fully represent its flow state.

Based on the contradiction between protection and development, conflicts often arise between the authenticity of the subject and the object, between the development motivation and the results (mainly about commercialisation), between the theoretical framework and the management tools (mainly about carrying capacity), and between reproduction and reconstruction (mainly about display and interpretation) (Zhang 2010). Nevertheless, affected by the specific source of intrinsic contestation mentioned above, the core issues raised in cultural heritage tourism in Chinese qiaoxiang heterogeneously form the objective of discussion in the next section (Fig. 1).

4 Core issues of cultural heritage tourism studies in Chinese qiaoxiang

4.1 Whose heritage

‘Whose heritage’ emphasises the issue of heritage identification and selection. Whether it is the identification, selection, interpretation, construction of heritage (Peng and Zheng 2008) or the production and consumption of heritage (Daher 2000), both are closely related to power. Watson (1975) notes that in the qiaoxiang in Hong Kong, the social meaning of physical housing is reproduced over time in a game of power relations, which changes qiaoxiang from a place of production to a place of consumption. Diasporic Chinese and other diaspora groups have played an important role in promoting the production and consumption of heritage (Andreea 2019). Relying on their own advantages, they have increased their power (Chan and Cheng 2015), broke the original balance of interests, and created a new balance in their hometown. The majority of local communities are regarded as marginal groups; they often give in to the authority of the capital or local leaders and lose the rights to manage the heritage. As the sponsor of migrant heritage, the Chinese diaspora has international influence that enables them to have more power than other average community residents. They can influence heritage identification and selection instead of being anxious or helpless as other underprivileged community residents usually are. Cultural heritage in China has also received more attention from conservation organisations. The concern over qiaoxiang follows the trend of balancing heritage protection and democracy and responds to the topic of community empowerment in tourism studies.

On the other hand, the flow of people, goods, and money caused by the diaspora has created a confusion over ‘whose heritage’, reflecting the contradiction between space and culture essentially. A built heritage occupies a certain physical space. Its foundation is buried in the soil of a specific space, and it is injected with the meaning of place through social constraints such as religions and rules. However, the immigrant heritage in the hometown of the Chinese diaspora is one of mobility. They are located in China but shaped by Western culture and remittances (Watson 2004). This is contrary to the culture of the space to which they belong. This inconsistency between space and culture has led to the question of whose heritage and whose responsibility, and it has created difficulty in heritage protection and conversion for use with tourism.

4.2 What value the heritage represents

‘What value the heritage represents’ emphasises the topic of the commercialisation of ‘home’. The contradictions between ‘root’ and modernity and flow and stillness gives rise to the problem of the commercialisation of ‘home’. Influenced by local development, the spatial structure and function of immigrant heritage have been changed. The public space highlighting a village’s traditions has become a commercial space, and houses have become a place for exhibitions (Wang 2014). When diasporic Chinese return to their homeland, their complex desire to retain a ‘stationary’ hometown becomes a significant obstacle to heritage tourism development.

Knapp and Lo (2005) have published two books on Chinese houses, focusing on residential practices that have lasted for three or four centuries. These houses were microcosms of Chinese society in different periods. They were built following the tradition of ‘fengshui’, and the furniture inside (including materials, construction techniques, decorations and placement) also showed a symbiotic relationship with the house. The structure and material of the house reflected the historical period in which it was built and condensed group living memories at that time (Morton 2007). Erdal (2012) summarises the practical and symbolic reasons for migrants to build houses in their ancestral country. The practical reasons include improving the living standard of their relatives in their hometown and returning to China for short-term vacation and investment, whereas the symbolic reasons include winning social capital and improving a sense of belonging. The built houses are generally related to cultural and social values. To protect these houses, overseas Chinese often entrust their relatives to look after the houses and create a unique principal-agent relationship based on kinship. However, with the diaspora of property owners and agents, the relationship is breaking, and many houses in Chinese qiaoxiang were destroyed because of disrepair.

Cultural heritage tourism in Chinese qiaoxiang gives the houses there the opportunity to be reused, but the commercialisation brought about by tourism was not welcomed by most overseas Chinese. Some owners of diaolou in Kaiping refused to change the original diaolou style and prefer to use the diaolou as a museum rather than a tourist attraction (Jiang 2019). For the government, turning such houses into museums provides a channel for patriotic education and contributes to the spread of official ideology (Wang 2014). Nevertheless, the transformation from home to heritage still leads to overcommercialisation, igniting the fuse of the contradiction among stakeholders (Snepenger et al. 2007). For instance, the continuous influx of tourists has changed the house’s attributes of residence and defence. In the tulou’s architectural design in Fujian Province, China, the tulou’s central lobby used to symbolise family unity but has since become a public commercial space both in use and in place meaning. The house has in essence changed from being a cultural symbol of ‘roots’ and comfort to a popular commodity in the tourist market (Su 2012). The Hakka people living inside have no choice but to negotiate with traditional and habitual lifestyles (Zhang 2014), resulting in larger conflicts in their struggle for resources.

4.3 How to interpret the value of heritage

‘How to interpret heritage’ emphasises the issue of authenticity. Authenticity is difficult to define due to its use in multiple contexts and levels. Immigrants have a definite emotional connection with their hometown (Huang, Hung, and Chen 2018), and they often act as tourism ambassadors assisting with the promotion of destinations (Seraphin, Korstanje, and Gowreesunkar 2020). In different social situations and historical backgrounds, immigrants’ local identity will also constantly evolve and change (Zhu et al. 2010), resulting in challenges to the interpretation of heritage due to fluidity. The way the Chinese diaspora conveys the meaning of the people, places, and events (Hall and McArthur 1996) they identify with may also change as a result.

Another issue is heritage interpretation. Interpretation studies in tourism emphasise the ‘reconstruction’ of heritage value, that is, to explain heritage value in a way tourists can understand and may even expect. It may include the presentation of artefacts and some staged performances, though these have been criticised by the cultural heritage field (Zhang 2010). In research on Kaiping diaolou and villages, tourists interpret diaolou as a place displaying the past lives and stories of Chinese diasporic families (Jiang and Zhang 2019). Concurrently, local experts consider diaolou to be the result of Chinese actively accepting Western culture, absorbing useful parts and creating the unique culture in Chinese qiaoxiang (Zhang 2004). This disparity demonstrates the contradiction between heritage representation and interpretation. The different results of the power game between stakeholders show different outcomes of the conflicts between heritage protection and utilisation.

5 Conclusion

In general, there is a relative lack of research exploring heritage tourism in Chinese qiaoxiang, even though they can highlight the uniqueness of diaspora heritage. Research needs to be promoted in both depth and breadth. Accordingly, this paper constructs a conceptual analytical framework to understand this special heritage type and points out the intrinsic contestation within it. The paper explores the contradiction between ‘ancestral root culture’ and modernity and between flow and stillness and analyses how this contradiction leads to the core issues of heritage tourism in Chinese qiaoxiang. Following the questions of ‘whose heritage’, ‘what value the heritage represents’, and ‘how to interpret the value of heritage’ in heritage tourism, the paper also frames these research topics of cultural heritage tourism in terms of Chinese qiaoxiang.

The contradiction of heritage tourism in the homelands of the Chinese diaspora is evolving along with the heritage and tourism development process. Based on this analytical framework, comparative studies can be carried out on cases with obvious differences in heritage types, tourism development stages, and diasporic degrees. Future research can empirically analyse the formation, evolution, and results of the contradictions and discuss the possible governance methods.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

References

Andreea, Enache Oana. 2019. The role of the diaspora in promoting tourism for the valorisation of cultural heritage. Case study Romania. Global Economic Observer 7 (1): 37–40.

Ari, Lilach Lev, and David Mittelberg. 2008. Between authenticity and ethnicity: Heritage tourism and re-ethnification among diaspora Jewish youth. Journal of Heritage Tourism 3 (2): 79–103.

Ashworth, Gregory. 2000. Heritage tourism and places: A review. Tourism Recreation Research 1 (25): 19–29.

Ashworth, Gregory, and Peter Larkham. 1994. Building a new heritage: Tourism, culture and identity in the new Europe. London: Routledge.

Brubaker, Rogers. 2005. The 'diaspora' diaspora. Ethnic and Racial Studies 28 (1): 1–19.

Byrne, Denis. 2013. Love and loss in the 1960s. The International Journal of Heritage Studies 19 (6): 596–609.

Byrne, Denis. 2016a. Heritage corridors: Transnational flows and the built environment of migration. Journal of Ethnic & Migration Studies 42 (14): 2360–2378.

Byrne, Denis. 2016b. The need for a transnational approach to the material heritage of migration: The China-Australia corridor. Journal of Social Archaeology 16 (3): 261–285.

Chan, Hiu Ling, and Christopher Cheng. 2015. Building homeland heritage: Multiple homes among the Chinese diaspora and the politics on heritage management in China. International Journal of Heritage Studies 22 (1): 1–13.

Chen, Shaoying. 2001. Legal protection of real estate rights and interests of overseas Chinese. Changchun: Jilin People's Press.

Clifford, James. 1995. Diasporas. Cultural Anthropology 9 (3): 302–338.

Corner, John, and Sylvia Harvey. 1991. Enterprise and heritage: Crosscurrents of National Culture. London: Routledge.

Daher, Rami Farout. 2000. Dismantling a community’s heritage. In Tourism and heritage relationships: Global,national and local perspectives, ed. Mike Robinson et al., 109. Conway: Athenaeum Press.

Dahrendorf, Ralf. 2000. The modern social conflicts. Beijing: China Social Science Press.

Dai, Xiangyi, and Weimin Que. 2012. The nomination and management of urban heritage: An inquiry into ‘the operational guidelines for the implementation of the world heritage convention’. Urban Planning International 27 (2): 61–66.

Duan, Ying. 2013. Diaspora: The evolution of its concept and the analysis of its theory. Ethno-National Studies 2: 14–25+123.

Erdal, Marta Bivand. 2012. ‘A place to stay in Pakistan’: Why migrants build houses in their country of origin. Population, Space and Place 18 (5): 629–641.

Esman, Miltton J. 2009. Diasporas in the contemporary world. Cambridge and Malden: Polity Press.

Evans, Graeme. 2002. Living in a world Heritage City: Stakeholders in the dialectic of the universal and particular. International Journal of Heritage Studies 8 (2): 117–135.

Faist, Thomas. 2000. The volume and dynamics of international migration and transnational social spaces. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fang, Lili. 2008. Heritage: Practice and experience. Kunming: Yunnan Education Publishing House.

Graham, Brian, Ashworth Gregory, and John Tunbridge. 2000. A geography of heritage: Power, culture and economy. London: Arnold, Oxford University Press.

Hall, Colin Michael, and Simon McArthur. 1996. Heritage Management in Australia and new Zealand: The human dimension. Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

Harvey, David. 2001. Heritage pasts and heritage presents: Temporality, meaning and the scope of heritage studies. International Journal of Heritage Studies 7 (4): 319–338.

Hornby, Albert Sidney. 2005. An advanced Oxford English-Chinese and Chinese-English dictionary. Beijing: The Commercial Press.

Hu, Zhiyi. 2011. A review of overseas studies on ‘intrinsic contestations’ in heritage tourism. Tourism Tribune 26 (9): 90–96.

Huang, Jiye, Weiqiang Tan, Mingri Li, and Huang Zhao. 2007. The road to the world heritage. Zhuhai: Zhuhai Publishing House.

Huang, Weijue, Kam Hung, and Chunchu Chen. 2018. Attachment to the home country or hometown? Examining diaspora tourism across migrant generations. Tourism Management 68: 52–65.

Innocenti, Perla. 2013. Migrating heritage: Experiences of cultural networks and cultural dialogue in Europe. Surrey: Ashgate Publishing Limited.

Jiang, Ting. 2019. The impact of Diasporic property relations on heritage protection and tourism utilization in overseas Chinese hometown. Guangzhou: Sun Yat-sen University.

Jiang, Ting, and Chaozhi Zhang. 2019. Tourist interpretation of place meaning in Kaiping Diaolou and villages. World Regional Studies 28 (3): 194–201.

Jiang, Ting, and Chaozhi Zhang. 2021. The formation and features of property rights’ three-dimensional relationship of built heritages in the hometown of overseas Chinese: Case study of Kaiping Diaolou. Social Sciences in Nanjing 2: 166–172.

King, Russell, and Anastasia Christou. 2011. Of counter-diaspora and reverse transnationalism: Return, mobilities to and from the ancestral homeland. Mobilities 6 (4): 451–466.

Knapp, Ronald G., and Kai-Yin Lo. 2005. House, home, family: Living and being Chinese. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

Levitt, Peggy, and Nina Glick Schiller. 2004. Conceptualizing simultaneity: A transnational social field perspective on society. International Migration Review 38 (3): 1002–1039.

Maruyama, Naho. 2015. Roots tourists' internal experiences and relations with the ancestral land: Case of second-generation Chinese Americans. International Journal of Tourism Research 18 (5): 469–476.

Maruyama, Naho, and Amanda Stronza. 2012. Roots tourism of Chinese Americans. Ethnology 49 (1): 23–44.

McKercher, Bob, Pamela Ho, and Hilary du Cros. 2005. Relationship between tourism and cultural heritage management: Evidence from Hong Kong. Tourism Management 26 (4): 539–548.

Merriman, Nick. 2004. Public archaeology. London and New York: Routledge.

Meskell, Lynn. 2004. Object worlds in ancient Egypt. Oxford: Berg.

Morton, Christopher. 2007. Remembering the house: Memory and materiality in northern Bostwana. Journal of Material Culture 12 (2): 157–179.

Muhammad, Rizwan. 2017. Acculturation and food consumption of south Asian diaspora in the UK: Moderating influence of religious identity and the neighbourhood. London: Middlesex University.

Nikielska-Sekula, Karolina. 2019. Migrating heritage? Recreating ancestral and new homeland heritage in the practices of immigrant minorities. International Journal of Heritage Studies 25 (11): 1113–1127.

Nuryanti, Wiendu. 1996. Heritage and postmodern tourism. Annals of Tourism Research 23 (2): 249–260.

Peckham, Robert. 2003. Rethinking heritage: Cultures and politics in Europe. London: IB Tauris.

Peng, Zhaorong, and Xiangchun Zheng. 2008. Legacy and tourism: Collocating and deviating of tradition and modern. Guangxi Ethnic Studies 3: 33–39.

Portes, Alejandro. 1996. Global villagers: The rise of transnational communities. The American Prospect 7 (25): 74–77.

Robinson, Mike, and Boniface Priscilla. 1999. Tourism and cultural conflicts. Oxon: CABI Publishing.

Seraphin, Hugues, Maximiliano Korstanje, and Vanessa Gowreesunkar. 2020. Diaspora and ambidextrous management of tourism in post-colonial, post-conflict and post-disaster destinations. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change 18 (2): 113–132.

Smith, Melanie. 2003. Issues in cultural tourism studies. New York: Routledge.

Snepenger, David, Mary Snepenger, Matt Dalbey, and Amanda Wessol. 2007. Meanings and consumption characteristics of places at a tourism destination. Journal of Travel Research 45 (3): 310–321.

Su, Xiaobo. 2012. 'It is my home. I will die here': Tourism development and the politics of place in Lijiang, China. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography 94 (1): 31–45.

Sun, Jiuxia, and Yi Zhou. 2014. Study on the reproduction of space of tourism community from the perspective of everyday life: Based on theories of Lefebvre and De Certeau. Acta Geographica Sinica 69 (10): 1575–1589.

Tilden, Freeman. 2009. Interpreting our heritage. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press.

Tuan, Yifu. 1977. Space and place: The perspective of experience. Minneapolis: Minnesota University Press.

Tuan, Yifu. 1990. Topophilia: A study of environmental perception, attitudes and values. New York: Columbia University Press.

Walsh, Kevin. 1992. The representation of the past: Museums and heritage in the postmodern world. London: Routledge.

Wang, Cangbai. 2014. How does a house remember? Heritage-ising return migration in an Indonesian-Chinese house museum in Guangdong, PRC. International Journal of Heritage Studies 20 (4): 454–474.

Wang, Cangbai. 2021. Museum representations of Chinese diasporas: Migration histories and the cultural heritage of the homeland. Oxon and New York: Routledge.

Wang, Yunxia. 2010. Analysis of the concept and classification of cultural heritage. Theory Monthly 11: 5–9.

Waterton, Emma, and Steve Watson. 2013. Framing theory: Towards a critical imagination in heritage studies. International Journal of Heritage Studies 19 (6): 546–561.

Watson, James L. 1975. Emigration and the Chinese lineage: The mans in Hong Kong and London. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Watson, James L. 2004. Presidential address: Virtual kinship, real estate, and diaspora formation – The man lineage revisited. The Journal of Asian Studies 63 (4): 893–910.

Xu, Songling. 2005. The third national policy: Chinese cultural and natural heritage preservation. Beijing: Science Press.

Zhang, Chaozhi. 2008. Tourism and heritage protection: Case-based theoretical research. Tianjin: Nankai University Press.

Zhang, Chaozhi. 2010. Cultural heritage and tourism development: Moving forward in dualistic conflict. Tourism Tribune 52 (4): 7–8.

Zhang, Chaozhi, and Zeng Deng. 2009. Tourism development and changes in farmer land consciousness — Case of Kaiping Diaolou and villages. Journal of Guangxi University for Nationalities (Philosophy and Social Science Edition) 31 (S1): 31–34.

Zhang, Chaozhi, and Wenjing Li. 2016. Heritage tourism research: From tourism in heritage sites to heritage tourism. Tourism Science 30 (1): 37–47.

Zhang, Chaozhi, Ling Ma, Xiaoxiao Wang, and Dezhen Yu. 2008. San io tic authenticity and commercialization of heritage tourism destinations based on a case study of Wuzhen and Zhouzhuang. Tourism Science 5: 59–66.

Zhang, Guoxiong. 2004. A study of Kaiping Diaolou in the hometown of overseas Chinese and the modern mass initiative to be receptive to the western culture. Journal of Hubei University (Philosophy and Social Science) 31 (5): 597–602.

Zhang, Guoxiong. 2006. The design of Kaiping Diaolou. Journal of Wuyi University (Social Sciences Edition) 8 (4): 30–34.

Zhang, Jinhe, Guorong Tang, Huan Hu, Peng Yu, and Lin Zhao. 2018. The intercultural study from geographical perspectives in the context of cultural globalization. Geographical Research 37 (10): 2011–2023.

Zhang, Kang. 2017. A study on the evolution of ‘Chinese diaspora - native country’ relations. Journal of Overseas Chinese History Studies 2: 10–18.

Zhang, Lijun. 2014. Living with/in heritage: Tulou as home, heritage, and destination. Bloomington: Indiana University.

Zhao, Jian. 2018a. A review of China’s policy on overseas Chinese affairs in the 40 years of reform and opening-up. Journal of Overseas Chinese History Studies 4: 14–22.

Zhao, Liu. 2018b. The intuitive construction of the tourism world: A phenomenological perspective based upon perceptual enrichment. Tourism Tribune 33 (3): 13–22.

Zhu, Hong, Junxi Qian, and Xiaoliang Chen. 2010. Place and identity: The rethink of place of European-American human geography. Human Geography 25 (6): 1–6.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The research is funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China [project serial number: 42001146].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The author read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author has declared that no competing interests exist.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, T. A conceptual framework for understanding the intrinsic contestation of cultural heritage tourism in Chinese qiaoxiang. Built Heritage 6, 28 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43238-022-00075-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43238-022-00075-9